Can AI data centres really work in space? The technical and environmental hurdles

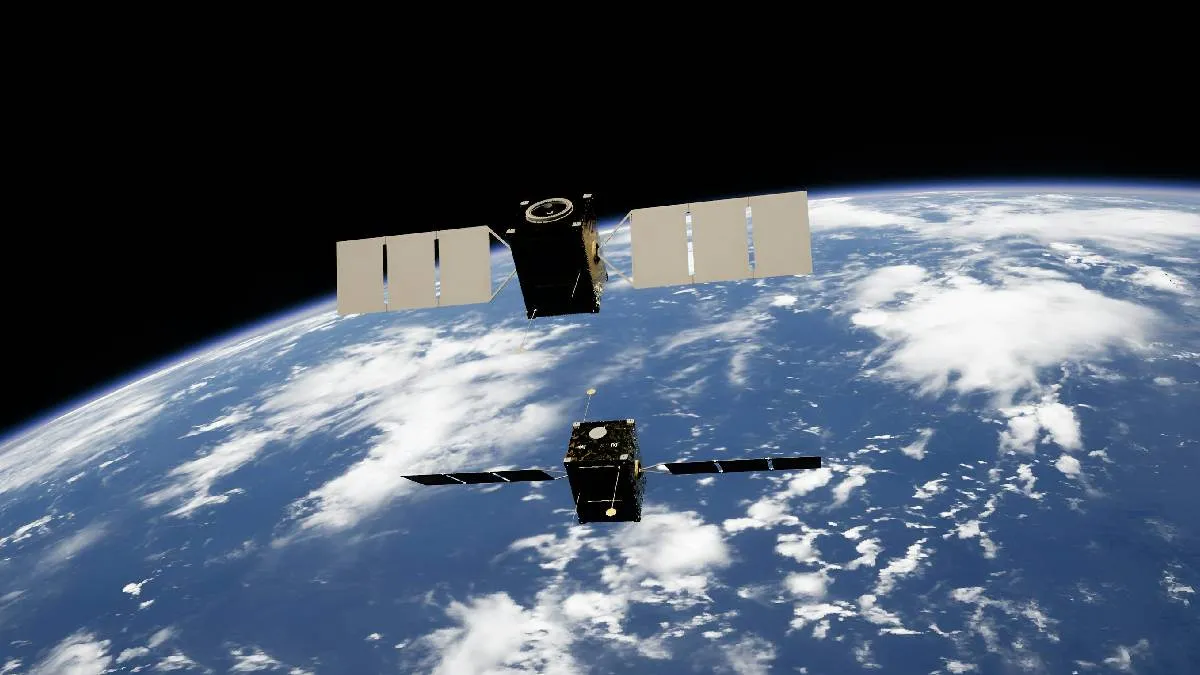

Elon Musk wants to build solar-powered AI data centres in space using up to a million satellites, but experts warn of technical, financial and environmental challenges.

Elon Musk vowed this week to disrupt yet another industry, just as he previously did with cars and rockets—and once again, he is taking on daunting odds. The world’s richest man said he wants to place as many as one million satellites into orbit to create vast, solar-powered data centres in space. The idea is to enable expanded use of artificial intelligence and chatbots without straining power grids, triggering blackouts or driving up electricity bills.

To fund the ambitious plan, Musk combined SpaceX with his AI business on Monday and is planning a major initial public offering of the merged company.

“Space-based AI is obviously the only way to scale,” Musk wrote on SpaceX’s website, adding about his solar ambitions, “It’s always sunny in space!”

However, scientists and industry experts say that even Musk—who outmaneuvered Detroit to turn Tesla into the world’s most valuable automaker—faces formidable technical, financial and environmental hurdles.

Feeling the heat in Space

Capturing solar energy from space to power chatbots and AI systems could ease pressure on terrestrial power grids and reduce the need for massive computing facilities that consume farmland, forests and large quantities of water for cooling.

But space presents its own challenges.

Data centres generate enormous heat. While space is cold, it is also a vacuum, which traps heat inside objects much like a Thermos flask keeps coffee hot by using airless insulation.

“An uncooled computer chip in space would overheat and melt much faster than one on Earth,” said Josep Jornet, a professor of computer and electrical engineering at Northeastern University.

One possible solution is to build enormous radiator panels that emit infrared light to push heat “out into the dark void,” Jornet said. While the technology has worked on a small scale, including aboard the International Space Station, he noted that Musk’s vision would require arrays of “massive, fragile structures that have never been built before”.

Floating debris and collision risks

Another major concern is space junk.

A single malfunctioning satellite that breaks apart or drifts off course could trigger a chain reaction of collisions, potentially disrupting emergency communications, weather forecasting and other critical services.

Musk noted in a recent regulatory filing that Starlink, his satellite communications network, has experienced only one “low-velocity debris generating event” in seven years of operation. Starlink has deployed around 10,000 satellites, but that figure is far below the roughly one million satellites Musk now proposes.

“We could reach a tipping point where the chance of collision is going to be too great,” said John Crassidis, a former NASA engineer at the University at Buffalo. “And these objects are going fast—17,500 miles per hour. There could be very violent collisions”.

No repair crews in orbit

Even without collisions, satellites inevitably fail. Chips degrade, components break and systems wear out over time.

Specialised graphics processing units (GPUs) used in AI systems can become damaged and need replacement.

“On Earth, what you would do is send someone down to the data centre,” said Baiju Bhatt, CEO of space-based solar energy company Aetherflux. “You replace the server, you replace the GPU, you’d do some surgery on that thing and you’d slide it back in”.

No such repair crews exist in orbit. GPUs in space are also vulnerable to damage from high-energy particles emitted by the sun.

Bhatt said one workaround is to overprovision satellites with extra chips to replace failed ones. But that approach is costly, as the chips can cost tens of thousands of dollars each, and current Starlink satellites have an operational lifespan of about five years.

Competition—and Musk’s leverage

Musk is not alone in trying to overcome these challenges.

A Redmond, Washington-based company called Starcloud launched a satellite in November carrying a single Nvidia-made AI chip to test its performance in space. Google is exploring orbital data centres under a project known as Project Suncatcher. Meanwhile, Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin announced plans in January to deploy a constellation of more than 5,000 satellites starting late next year, though its focus has been more on communications than AI.

Still, Musk holds a key advantage: rockets.

Starcloud relied on a SpaceX Falcon rocket to launch its test satellite. Aetherflux plans to send its “Galactic Brain” chips into space aboard a SpaceX rocket later this year. Google may also need SpaceX to launch its first two prototype satellites by early next year.

Launch costs as a strategic weapon

According to Pierre Lionnet, research director at trade association Eurospace, Musk routinely charges competitors far more for launches than SpaceX charges itself—up to USD 20,000 per kilogram of payload, compared with around USD 2,000 internally.

Lionnet said Musk’s announcements this week signal an intention to leverage that advantage in a new space race.

“When he says we are going to put these data centres in space, it’s a way of telling the others we will keep these low launch costs for myself,” Lionnet said. “It’s a kind of powerplay”.